Until a pair of years in the past, Lucy Calkins was, to many American lecturers and fogeys, a minor deity. 1000’s of U.S. faculties used her curriculum, known as Items of Examine, to show kids to learn and write. 20 years in the past, her guiding rules—that kids be taught finest once they love studying, and that lecturers ought to attempt to encourage that love—turned a centerpiece of the curriculum in New York Metropolis’s public faculties. Her strategy unfold by way of an institute she based at Columbia College’s Lecturers Faculty, and traveled additional nonetheless by way of instructing supplies from her writer. Many lecturers don’t check with Items of Examine by identify. They merely say they’re “instructing Lucy.”

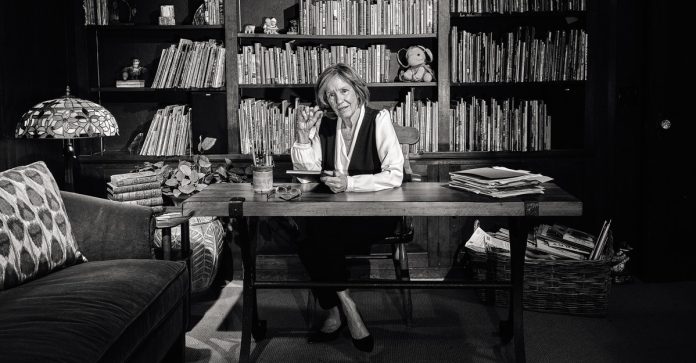

However now, on the age of 72, Calkins faces the destruction of all the pieces she has labored for. A 2020 report by a nonprofit described Items of Examine as “superbly crafted” however “unlikely to result in literacy success for all of America’s public schoolchildren.” The criticism turned not possible to disregard two years later, when the American Public Media podcast Bought a Story: How Educating Children to Learn Went So Incorrect accused Calkins of being one of many causes so many American kids wrestle to learn. (The Nationwide Evaluation of Instructional Progress—a check administered by the Division of Schooling—present in 2022 that roughly one-third of fourth and eighth graders are unable to learn on the “primary” stage for his or her age.)

In Bought a Story, the reporter Emily Hanford argued that lecturers had fallen for a single, unscientific thought—and that its persistence was holding again American literacy. The thought was that “starting readers don’t must sound out phrases.” That meant lecturers had been now not encouraging early learners to make use of phonics to decode a brand new phrase—to say cuh–ah–tuh for “cat,” and so forth. As a substitute, kids had been anticipated to determine the phrase from the primary letter, context clues, or close by illustrations. However this “cueing” system was not working for big numbers of youngsters, leaving them floundering and pissed off. The consequence was a studying disaster in America.

The podcast mentioned that “an organization and 4 of its high authors” had bought this “fallacious thought” to lecturers and politicians. The corporate was the academic writer Heinemann, and the authors included the New Zealander Marie Clay, the American duo Irene Fountas and Homosexual Su Pinnell, and Calkins. The podcast devoted a complete episode, “The Celebrity,” to Calkins. In it, Hanford puzzled if Calkins was wedded to a “romantic” notion of literacy, the place kids would fall in love with books and would then in some way, magically, be taught to learn. Calkins couldn’t see that her system failed poorer kids, Hanford argued, as a result of she was “influenced by privilege”; she had written, for example, that kids may be taught concerning the alphabet by selecting out letters from their environment, similar to “the monogram letters on their tub towels.”

In Hanford’s view, it was no shock if Calkins’s technique labored effective for wealthier youngsters, lots of whom arrive in school already beginning to learn. In the event that they struggled, they might all the time flip to non-public tutors, who may give the phonics classes that their faculties had been neglecting to offer. However youngsters with out entry to non-public tutors wanted to be drilled in phonics, Hanford argued. She backed up her claims by referencing neurological analysis into how kids be taught to learn—gesturing to a physique of proof generally known as “the science of studying.” That analysis demonstrated the significance of normal, specific phonics instruction, she mentioned, and ran opposite to how American studying lecturers had been being skilled.

For the reason that podcast aired, “instructing Lucy” has fallen out of trend. Calkins’s critics say that her refusal to acknowledge the significance of phonics has tainted not simply Items of Examine—a studying and writing program that stretches as much as eighth grade—however her total academic philosophy, generally known as “balanced literacy.” Forty states and the District of Columbia have handed legal guidelines or applied insurance policies selling the science of studying prior to now decade, in keeping with Schooling Week, and publishers are racing to regulate their choices to embrace that philosophy.

In some way, the broader debate over methods to train studying has develop into a referendum on Calkins herself. In September 2023, Lecturers Faculty introduced that it might dissolve the reading-and-writing-education heart that she had based there. Anti-Lucy sentiment has proliferated, notably within the metropolis that when championed her strategies: Final 12 months, David Banks, then the chancellor of New York Metropolis public faculties, likened educators who used balanced literacy to lemmings: “All of us march proper off the facet of the mountain,” he mentioned. The New Yorker has described Calkins’s strategy as “literacy by vibes,” and in an editorial, the New York Publish described her initiative as “a catastrophe” that had been “imposed on generations of American kids.” The headline declared that it had “Ruined Numerous Lives.” When the celebrated Harvard cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker shared an article about Calkins on X, he bemoaned “the scandal of ed faculties that promote studying quackery.” Queen Lucy has been dethroned.

“I imply, I can say it—it was a little bit bit like 9/11,” Calkins informed me once we spoke at her dwelling this summer time. On that day in 2001, she had been driving into New York Metropolis, and “actually, I used to be on the West Facet Freeway and I noticed the airplane crash into the tower. Your thoughts can’t even comprehend what’s taking place.” 20 years later, the suggestion that she had harmed kids’s studying felt like the identical form of intestine punch.

Calkins now concedes that a number of the issues recognized in Bought a Story had been actual. However she says that she had adopted the analysis, and was making an attempt to rectify points even earlier than the podcast debuted: She launched her first devoted phonics models in 2018, and later revealed a sequence of “decodable books”—simplified tales that college students can simply sound out. Nonetheless, she has not managed to fulfill her critics, and on the third day we spent collectively, she admitted to feeling despondent. “What surprises me is that I really feel as if I’ve executed all of it,” she informed me. (Heinemann, Calkins’s writer, has claimed that the Bought a Story podcast “radically oversimplifies and misrepresents complicated literacy points.”)

The backlash towards Calkins strikes some onlookers, even those that should not paid-up Lucy partisans, as unfair. “She wouldn’t have been my alternative for the image on the ‘wished’ poster,” James Cunningham, a professor emeritus of literacy research on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, informed me. Certainly, over the course of a number of days spent with Calkins, and plenty of extra hours speaking with individuals on all sides of this debate, I got here to see her downfall as half of a bigger story concerning the competing currents in American schooling and the common need for a simple, off-the-shelf resolution to the nation’s studying issues.

The query now’s whether or not Calkins is a lot part of the issue that she can’t be a part of the answer. “I’m going to determine this out,” she remembered pondering. “And I’m going to make clear it or I’m going to put in writing some extra or converse or do one thing or, or—repair it.” However can she? Can anybody?

On the final day of the varsity 12 months in Oceanside, a well-to-do city on Lengthy Island, everybody was simply delighted to see Lucy Calkins. The younger Yale-educated principal of Fulton Avenue College 8, Frank Zangari, greeted her warmly, and on the finish of 1 lesson, a instructor requested for a selfie.

The teachings I noticed pressured the significance of self-expression and empathy with different viewpoints; a bunch of sixth graders informed me concerning the books that they had learn that 12 months, which explored being poor in India and rising up Black in Sixties America. In each class, I watched Calkins converse to kids with a mix of intense consideration and simple problem; she received down on the ground with a bunch studying about orcas and frogs and peppered them with questions on how animals breathe. “Might you discuss a minute concerning the author’s craft?” she requested the sixth graders finding out poetry. “Be extra particular. Give examples,” she informed a fourth grader struggling to put in writing a memoir.

Together with her slim body, brown bob, and no-nonsense have an effect on, she jogged my memory of Nancy Pelosi. “I can’t retire; I don’t have any hobbies,” I overheard her saying to somebody later.

College 8 confirmed the strengths of Calkins’s strategy—which is presumably why she had advised we go to it collectively. Nevertheless it additionally hinted on the downsides. For generations in American public schooling, there was a push and pull between two broad camps—one through which lecturers are inspired to straight impart abilities and data, and a extra progressive one through which kids are thought to be taught finest by way of firsthand expertise. With regards to studying, the latter strategy dominates universities’ education schemes and resonates with many lecturers; serving to kids see themselves as readers and writers feels extra emotionally satisfying than drilling them on diphthongs and trigraphs.

This rigidity between the traditionalists and the progressives runs by way of many years of wrangling over standardized checks and thru a lot of the main curricular controversies in current reminiscence. Longtime educators tick off the assorted flash factors like Civil Conflict battlefields: outcome-based schooling, No Little one Left Behind, the Widespread Core. Each time, the pendulum went a method after which the opposite. “I began instructing elementary college in 1964,” says P. David Pearson, a former dean on the Berkeley College of Schooling, in California. “After which I went to grad college in, like, ’67, and there’s been a back-to-the-basics swing about each 10 years within the U.S., persistently.”

The progressives’ main perception is that classes centered on repetitive instruction and simplified textual content extracts will be boring for college students and lecturers alike, and that many kids reply extra enthusiastically to discovering their very own pursuits. “We’re speaking about an strategy that treats youngsters as competent, mental that means makers, versus youngsters who simply have to be taught the code,” Maren Aukerman, a professor on the College of Calgary, informed me. However opponents see that strategy as nebulous and undirected.

My time at College 8 was clearly meant to display that Items of Examine is just not hippie nonsense, however a rigorous curriculum that may succeed with the best lecturers. “There’s no query in my thoughts that the philosophy works, however so as to implement it, it takes plenty of work,” Phyllis Harrington, the district superintendent, informed me.

College 8 is a contented college with nice outcomes. Nonetheless, whereas the varsity makes use of Calkins’s writing models for all grades, it makes use of her studying models solely from the third grade on. For first and second grades, the varsity makes use of Fundations, which is marketed as “a confirmed strategy to Structured Literacy that’s aligned with the science of studying.” In different phrases, it’s a phonics program.

Calkins’s upbringing was financially comfy however psychologically powerful. Each of her dad and mom had been docs, and her father ultimately chaired the division of drugs on the College at Buffalo. Calkins’s mom was “an important, great particular person in my life, however actually brutal,” she informed me. If a mattress wasn’t made, her mom ripped off the sheets. If a coat wasn’t hung up, her mom dropped it into the basement. When the younger Lucy bit her fingernails, her mom tied dancing gloves onto her fingers. When she scratched the mosquito bites on her legs, her mom made her put on thick pantyhose on the top of summer time.

The 9 Calkins kids raised sheep and chickens themselves. Her recollections of childhood are of horseback using within the chilly, infinite hand-me-downs, and little tolerance for unhealthy habits.

That’s the reason, Calkins informed me, “nothing that Emily Hanford has mentioned grates on me greater than the rattling monogrammed towels.” However she is aware of that the cost of being privileged and out of contact has caught. Her mates had warned her about letting me into her dwelling in Dobbs Ferry, a reasonably suburb of New York, and I might see why. Her home is idyllic—on the finish of a protracted personal drive, shaded by previous bushes, with a grand piano within the hallway and a Maine-coon cat patrolling the picket flooring. Calkins has profited handsomely from textbook gross sales and coaching charges, and within the eyes of some individuals, that’s suspicious. (“Cash is the very last thing I ever take into consideration,” she informed me.)

She turned enthusiastic about studying and writing as a result of she babysat for the kids of the literacy pioneer Donald Graves, whose philosophy will be summarized by considered one of his most generally cited phrases: “Kids wish to write.” Even at a younger age, she believed in exhaustively ready enjoyable. “I’d plan a bagful of issues I’d deliver over there; I used to be one of the best babysitter you would ever have,” she mentioned. “We’d do crafts initiatives, and drama, you already know, and I’d maintain the youngsters busy all day.”

When Calkins was 14, Graves despatched her to be a counselor at a summer time camp in rural Maine. She remembers two youngsters specifically, Sophie and Charlie. Sophie was “so powerful and surly, and a form of obese, insecure, powerful child,” however she opened up when Calkins took her horseback using after which requested her to put in writing about it. Charlie liked airplanes, and so she requested him to put in writing about these. The expertise cemented her lifelong perception that kids ought to learn and write as a type of self-expression.

After graduating from Williams Faculty in 1973, she enrolled in a program in Connecticut that skilled lecturers to work in deprived districts. She learn all the pieces about instructing strategies she might discover, and traveled to England, the place a progressive schooling revolution was in full swing.

Calkins returned to America decided to unfold this empowering philosophy. She earned a doctorate at NYU, and, in 1986, revealed a ebook known as The Artwork of Educating Writing. Later, she expanded her purview to studying instruction.

On the time, the zeitgeist favored an strategy generally known as “entire language.” This advocated impartial studying of full books and advised that kids ought to determine phrases from context clues moderately than arduously sounding them out. Progressives liked it, as a result of it emphasised playfulness and company. However in follow, entire language had apparent flaws: Some kids do seem to choose up studying simply, however many profit from centered, direct instruction.

This strategy influenced Calkins as she developed her instructing philosophy. “Lucy Calkins sides, in most particulars, with the proponents of ‘entire language,’ ” The New York Instances reported in 1997. Her heavyweight 2001 ebook, The Artwork of Educating Studying, has solely a single chapter on phonics in main grades; it does observe, nevertheless, that “researchers emphasize how necessary it’s for kids to develop phonemic consciousness in kindergarten.”

The writer Natalie Wexler has described Calkins’s ensuing strategy, balanced literacy, as an try to create a “peace treaty” within the studying wars: Phonics, sure, should you should, but additionally writing workshops and impartial studying with industrial kids’s books, moderately than the stuffier grade-level decodable texts and authorized extracts. (Defenders of the previous technique argue that utilizing full books is extra cost-efficient, as a result of they are often purchased cheaply and utilized by a number of college students.) “If we make our kids imagine that studying has extra to do with matching letters and sounds than with creating relationships with characters like Babar, Madeline, Charlotte, and Ramona,” Calkins wrote, “we do extra hurt than good.”

Sentences like which are why critics noticed balanced literacy as a branding train designed to rehabilitate previous strategies. “It was a strategic rebadging of entire language,” Pamela Snow, a cognitive-psychology professor at La Trobe College, in Australia, informed me. Even lots of Calkins’s defenders concede that she was too sluggish to embrace phonics because the proof for its effectiveness grew. “I believe she ought to have reacted earlier,” Pearson, the previous Berkeley dean, informed me, however he added: “As soon as she modified, they had been nonetheless beating her for what she did eight years in the past, not what she was doing final month.”

For the primary many years of her profession, Calkins was an influential thinker amongst progressive educators, writing books for lecturers. In 2003, although, Joel Klein, then the chancellor of the New York Metropolis public faculties, all of a sudden mandated her workshop strategy in nearly all the metropolis’s elementary faculties, alongside a separate, a lot smaller, phonics program. An article within the Instances advised that some noticed Klein as “an unwitting captive of the town’s liberal consensus,” however Klein brushed apart the criticisms of balanced literacy. “I don’t imagine curriculums are the important thing to schooling,” he mentioned. “I imagine lecturers are.” Now all people within the metropolis’s public faculties can be “instructing Lucy.”

As different districts adopted New York’s lead, Items of Examine turned one of the vital in style curricula in the USA. This led, inevitably, to backlash. A philosophy had develop into a product—a particularly in style and financially profitable one. “As soon as upon a time there was a considerate educator who raised some attention-grabbing questions on how kids had been historically taught to learn and write, and proposed some modern modifications,” the writer Barbara Feinberg wrote in 2007. “However as she turned well-known, vital debate largely ceased: her phrase turned regulation. Over time, a few of her strategies turned dogmatic and excessive, but her affect continued to develop.”

You wouldn’t comprehend it from listening to her fiercest detractors, however Calkins has, in reality, constantly up to date Items of Examine. Not like Irene Fountas and Homosexual Su Pinnell, who’ve stayed quiet in the course of the newest furor and quietly reissued their curriculum with extra emphasis on phonics final 12 months, Calkins has even taken on her critics straight. In 2019—the 12 months after she added the devoted phonics texts to Items of Examine—she revealed an eight-page doc known as “No One Will get to Personal the Time period ‘The Science of Studying,’ ” which referred dismissively to “phonics-centric individuals” and “the brand new hype about phonics.” This tone drove her opponents mad: Now that Calkins had been pressured to adapt, she wished to resolve what the science of studying was?

“Her doc is just not concerning the science that I do know; it’s about Lucy Calkins,” wrote the cognitive neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg, one of many critics interviewed in Bought a Story. “The aim of the doc is to guard her model, her market share, and her standing amongst her many followers.”

Speaking with Calkins herself, it was laborious to nail all the way down to what extent she felt that the criticisms of her earlier work had been justified. Once I requested her how she was fascinated with phonics within the 2000s, she informed me: “Each college has a phonics program. And I’d all the time discuss concerning the phonics packages.” She added that she introduced phonics specialists to Columbia’s Lecturers Faculty a number of occasions a 12 months to assist prepare aspiring educators. (James Cunningham, at UNC Chapel Hill, backed this up, telling me, “She was actually not sporting a sandwich billboard round: DON’T TEACH PHONICS.”)

However nonetheless, I requested Calkins, would it not be honest to say that phonics wasn’t your bag?

“I felt like phonics was one thing that you’ve the phonics consultants train.”

So the place does this characterization of you being hostile towards phonics come from?

“Hopefully, you perceive I’m not silly. You would need to be silly to not train a 5-year-old phonics.”

However some individuals didn’t, did they? They had been closely into context and cueing.

“I’ve by no means heard of a kindergarten instructor who doesn’t train phonics,” Calkins replied.

As a result of that is America, the studying debate has develop into a tradition conflict. When Bought a Story got here alongside in 2022, it resonated with quite a lot of audiences, together with center-left schooling reformers and fogeys of youngsters with studying disabilities. Nevertheless it additionally galvanized political conservatives. Calkins’s Items of Examine was already below assault from the best: In 2021, an article within the Manhattan Institute’s Metropolis Journal titled “Items of Indoctrination” had criticized the curriculum, alleging that the best way it teaches college students to investigate texts “quantities to little greater than radical proselytization by way of literature.”

The podcast was launched at an anxious time for American schooling. Through the coronavirus pandemic, many faculties—notably in blue states—had been closed for months at a time. Masking in lecture rooms made it tougher for kids to lip-read what their lecturers had been saying. Check scores fell, and have solely not too long ago begun to get better.

“Dad and mom had, for a time frame, a front-row seat primarily based on Zoom college,” Annie Ward, a not too long ago retired assistant superintendent in Mamaroneck, New York, informed me. She puzzled if that fueled a need for a “again to fundamentals” strategy. “If I’m a dad or mum, I wish to know the instructor is instructing and my child is sitting there soaking it up, and I don’t need this loosey-goosey” stuff.

Disgruntled dad and mom rapidly gathered on-line. Mothers for Liberty, a right-wing group that started off by opposing college closures and masks mandates, started lobbying state legislators to alter college curricula as nicely. The studying wars started to merge with different controversies, similar to how laborious faculties ought to push diversity-and-inclusion packages. (The Mothers for Liberty web site recommends Bought a Story on its sources web page.) “We’re failing youngsters on a regular basis, and Mothers for Liberty is looking it out,” a co-founder, Tiffany Justice, informed Schooling Week in October of final 12 months. “The concept that there’s extra emphasis positioned on range within the classroom, moderately than instructing youngsters to learn, is alarming at finest. That’s legal.”

Ward’s district was not “instructing Lucy,” however utilizing its personal bespoke balanced-literacy curriculum. Within the aftermath of the pandemic, Ward informed me, the district had a number of “contentious” conferences, together with one in January 2023 the place “we had ringers”—attendees who weren’t dad and mom or group members, however as a substitute gave the impression to be activists from outdoors the district. “None of us within the room acknowledged these individuals.” That had by no means occurred earlier than.

I had met Ward at a dinner organized by Calkins at her dwelling, which can also be the headquarters of Mossflower—the successor to the middle that Calkins used to guide at Lecturers Faculty. The night demonstrated that Calkins nonetheless has star energy. On quick discover, she had managed to assemble half a dozen superintendents, assistant superintendents, and principals from New York districts.

“Any form of disruption like this has you assume very fastidiously about what you’re doing,” Edgar McIntosh, an assistant superintendent in Scarsdale, informed me. However he, like a number of others, was pissed off by the controversy. Throughout his time as an elementary-school instructor, he had found that some kids might decode phrases—the fundamental ability developed by phonics—however struggled with their that means. He apprehensive that folks’ clamor for extra phonics may come on the expense of lecturers’ consideration to fluency and comprehension. Raymond Sanchez, the superintendent of Tarrytown’s college district, mentioned principals ought to have the ability to clarify how they had been including extra phonics or decodable texts to present packages, moderately than having “to throw all the pieces out and discover a sequence that has a sticker that claims ‘science of studying’ on it.”

This, to me, is the important thing to the anti-Lucy puzzle. Hanford’s reporting was thorough and needed, however its conclusion—that entire language or balanced literacy would get replaced by a shifting, research-based motion—is difficult to reconcile with how American schooling truly works. The science of studying began as a impartial description of a set of rules, but it surely has now develop into a model identify, one other off-the-shelf resolution to America’s academic issues. The reply to these issues may not be to swap out one industrial curriculum package deal for an additional—however that’s what the system is about as much as allow.

Gail Dahling-Hench, the assistant superintendent in Madison, Connecticut, has skilled this strain firsthand. Her district’s faculties don’t “train Lucy” however as a substitute observe a bespoke native curriculum that, she says, makes use of classroom parts related to balanced literacy, such because the workshop mannequin of scholars finding out collectively in small teams, whereas additionally emphasizing phonics. That didn’t cease them from operating afoul of the brand new science-of-reading legal guidelines.

In 2021, Connecticut handed a “Proper to Learn” regulation mandating that faculties select a Ok–3 curriculum from an authorized listing of choices which are thought of compliant with the science of studying. Afterward, Dahling-Hench’s district was denied a waiver to maintain utilizing its personal curriculum. (Eighty-five districts and constitution faculties in Connecticut utilized for a waiver, however solely 17 had been profitable.) “I believe they received wrapped across the axle of pondering that packages ship instruction, and never lecturers,” she informed me.

Dahling-Hench mentioned the state gave her no helpful rationalization for its resolution—nor has it outlined the penalties for noncompliance. She has determined to stay with the bespoke curriculum, as a result of she thinks it’s working. In accordance with check scores launched a couple of days after our dialog, her district is among the many best-performing within the state.

Protecting the present curriculum additionally avoids the price of making ready lecturers and directors to make use of a brand new one—a transition that will be costly even for a tiny district like hers, with simply 5 faculties. “It will possibly appear to be $150,000 to $800,000 relying on which program you’re , however that’s a onetime price,” Dahling-Hench mentioned. Then you want to consider annual prices, similar to new workbooks.

You possibly can’t perceive this controversy with out appreciating the sums concerned. Refreshing a curriculum can price a state thousands and thousands of {dollars}. Folks on each side will subsequently recommend that their opponents are motivated by cash—both saving their favored curriculum to maintain the earnings flowing, or getting wealthy by way of promoting college boards a wholly new one. Speaking with lecturers and researchers, I heard widespread frustration with America’s industrial strategy to literacy schooling. Politicians and bureaucrats have a tendency to like the thought of a packaged resolution—Purchase this and make all of your issues go away!—however the excellent curriculum doesn’t exist.

“In the event you gave me any curriculum, I might discover methods to enhance it,” Aukerman, on the College of Calgary, informed me. She thinks that when a instructing technique falls out of trend, its champions are sometimes personally vilified, no matter their good religion or experience. Within the case of Lucy Calkins and balanced literacy, Aukerman mentioned, “If it weren’t her, it might be another person.”

One apparent query concerning the science of studying is, nicely … what’s it? The proof for some form of specific phonics instruction is compelling, and states similar to Mississippi, which has adopted early screening to determine kids who wrestle to learn—and which holds again third graders if needed—look like enhancing their check scores. Past that, although, issues get messy.

Dig into this topic, and you will discover frontline lecturers and credentialed professors who contest each a part of the consensus. And I imply each half: Some lecturers don’t even assume there’s a studying disaster in any respect.

American faculties may be ditching Items of Examine, however balanced literacy nonetheless has its defenders. A 2022 evaluation in England, which mandates phonics, discovered that systematic critiques “don’t assist an artificial phonics orientation to the instructing of studying; they recommend {that a} balanced-instruction strategy is most probably to achieve success.”

The info on the consequences of particular strategies will be conflicting and complicated, which isn’t uncommon for schooling research, or psychological analysis extra usually. I really feel sorry for any well-intentioned superintendent or state legislator making an attempt to make sense of all of it. One of many lecture rooms at Oceanside College 8 had a wall show dedicated to “development mindset,” a trendy intervention that encourages kids to imagine that as a substitute of their intelligence and talent being mounted, they’ll be taught and evolve. Hoping to enhance check scores, many faculties have spent hundreds of {dollars} every implementing “development mindset” classes, which proponents as soon as argued ought to be a “nationwide schooling precedence.” (Some proponents additionally hoped, earnestly, that the strategy might assist deliver peace to the Center East.) However within the 20 years since development mindset first turned ubiquitous, the lofty claims made about its promise have come all the way down to earth.

Maintaining with all of that is greater than any instructor—greater than any college board, even—can moderately be anticipated to do. After I received in contact along with her, Emily Hanford despatched me seven emails with hyperlinks to research and background studying; I left Calkins’s home loaded down with models of her curricula for youthful college students. Extra adopted within the mail.

Even essentially the most modest pronouncements about what’s taking place in American faculties are tough to confirm, due to the sheer variety of districts, lecturers, and pupils concerned. In Bought a Story, Hanford advised that some faculties had been succeeding with Items of Examine solely as a result of dad and mom employed private tutors for his or her kids. However corroborating this with knowledge is not possible. “I haven’t found out a solution to quantify it, besides in a really robust anecdotal manner,” Hanford informed me.

Some lecturers love “instructing Lucy,” and others hate it. Is one group delusional? And if that’s the case, which one? Jenna and Christina, who’ve each taught kindergarten in New York utilizing Items of Examine, informed me that the curriculum was too invested within the thought of youngsters as “readers” and “writers” with out giving them the fundamental abilities wanted to learn and write. (They requested to be recognized solely by their first names in case {of professional} reprisals.) “It’s a bit of shit,” Christina mentioned. She added: “We’re anticipating them to use abilities that we haven’t taught them and that they aren’t coming to high school with. I’ve been making an attempt to specific that there’s an issue and I get known as adverse.” Jenna had resorted to a covert technique, secretly instructing phonics for as much as 90 minutes a day as a substitute of the transient classes she was instructed to offer.

However for each Jenna or Christina, there’s a Latasha Holt. After a decade as a third- and fourth-grade instructor in Arkansas, Holt is now an affiliate professor of elementary literacy on the College of Louisiana at Lafayette, the place she has watched from the sidelines because the tide turned towards Calkins. “The dismantling of this factor, it received to me, as a result of I had taught below Items of Examine,” she informed me. “I’ve used it, and I knew how good it was. I had lived it; I’ve seen it work; I knew it was good for teenagers.”

Aubrey Kinat is a third-grade instructor in Texas who not too long ago left her place at a public college as a result of it determined to drop Items of Examine. (The varsity now makes use of one other curriculum, which was deemed to align higher with the science of studying.) All of a sudden, she was pushed away from full novels and towards authorized excerpts, and her classes turned far more closely scripted. “I felt like I used to be speaking a lot,” she informed me. “It took the enjoyment out of it.”

For a lot of college boards dealing with newly politicized dad and mom who got here out of the pandemic with robust opinions, ditching Lucy has had the pleased facet impact of giving adults far more management over what kids learn. Calkins and a few of her dinner friends had advised that this may be the true motive for the animus round impartial studying. “I do begin to surprise if this actually is about wanting to maneuver all people in direction of textbooks,” Calkins mentioned.

Eighteen months after her sequence launched, Hanford returned in April 2024 with two follow-up episodes of Bought a Story, which took a much less polemical tone. Unsurprisingly so: Calkins had misplaced, and he or she had gained.

The science of studying is the brand new consensus in schooling, and its advocates are the brand new institution. It’s now on the hook for the curriculum modifications that it prompted—and for America’s studying efficiency extra usually. That’s an uncomfortable place for many who care extra about analysis than about successful political fights.

A few of the neuroscience underpinning Bought a Story was offered by Seidenberg, a professor emeritus on the College of Wisconsin at Madison. (He didn’t reply to an interview request.) For the reason that sequence aired, he has welcomed the transfer away from Items of Examine, however he has additionally warned that “not one of the different main industrial curricula which are at present out there had been primarily based on the related science from the bottom up.”

As a result of the usefulness of phonics is without doubt one of the few science-of-reading conclusions that’s instantly understandable to laypeople, “phonics” has come to face in for the entire philosophy. In a weblog submit final 12 months, Seidenberg lamented that, on a current Zoom name, a instructor had requested in the event that they wanted to maintain instructing phonemic consciousness as soon as kids had been good readers. (The reply isn’t any: Sounding out letters is what you do till the method turns into automated.) Seidenberg now apprehensive that the science of studying is “vulnerable to turning into a brand new pedagogical dogma.”

Hanford has additionally expressed ambivalence concerning the results of Bought a Story. She in contrast the scenario to the aftermath of No Little one Left Behind, a George W. Bush–period federal schooling initiative that closely promoted a literacy program known as Studying First. “It turned centered on merchandise and packages,” Hanford informed me, including that the ethos become “eliminate entire language and purchase one thing else.” Nonetheless, she is glad that the significance of phonics—and the analysis backing it—is now extra broadly understood, as a result of she thinks this could break the cycle of revolution and counterrevolution. She added that every time she talks with lawmakers, she stresses the significance of constant to hearken to lecturers.

What about her portrait of Calkins as wealthy, privileged, oblivious? Overlook the monogrammed towels, I informed Hanford; there’s a extra benign rationalization for Calkins’s worldview: In every single place she goes, she meets individuals, just like the lecturers and kids in Oceanside, who’re overjoyed to see her, and eager to inform her how a lot they love Items of Examine.

However Hanford informed me that she’d included the towels line as a result of “the overwhelming majority of lecturers, particularly elementary-school lecturers, in America are white, middle-class ladies.” Many of those ladies, she thought, had loved college themselves and didn’t intuitively know what it was wish to wrestle with studying to learn and write.

Reporting this story, I used to be reminded repeatedly that schooling is each a mass phenomenon and a deeply private one. Folks I spoke with would say issues like Properly, he’s by no means executed any classroom analysis. She’s by no means been a instructor. They don’t perceive issues the best way I do. The schooling professors would complain that the cognitive scientists didn’t perceive the historical past of the studying wars, whereas the scientists would complain that the schooling professors didn’t perceive the most recent peer-reviewed analysis. In the meantime, a instructor should command a category that features college students with dyslexia in addition to those that discover studying a breeze, and youngsters whose dad and mom learn to them each evening alongside kids who don’t converse English at dwelling. On the identical time, college boards and state legislators, confronted with offended dad and mom and a welter of conflicting testimony, should reply a easy query: Ought to we be “instructing Lucy,” or not?

Regardless of how painful the previous few years have been, although, Calkins is decided to maintain preventing for her legacy. At 72, she has each the vitality to begin over once more at Mossflower and the pragmatism to have promised her property to additional the trigger as soon as she’s gone. She nonetheless has a “ferocious” drive, she informed me, and a deep conviction in her strategies, at the same time as they evolve. She doesn’t need “to faux it’s a brand-new strategy,” she mentioned, “when in reality we’ve simply been studying; we’re simply incorporating extra issues that we’ve realized.”

However now that balanced literacy is as retro as entire language, Calkins is making an attempt to give you a brand new identify for her program. She thought she may strive “complete literacy”—or perhaps “rebalancing literacy.” No matter it takes for America to as soon as once more really feel assured about “instructing Lucy.”

This text seems within the December 2024 print version with the headline “Educating Lucy.” While you purchase a ebook utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.