Srinagar, Indian-administered Kashmir – Afiya’s* frail fingers decide on the unfastened threads of her worn dark-brown sweater. She sits on the fringe of her mattress within the rehabilitation ward of Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) Hospital in Indian-administered Kashmir’s principal metropolis of Srinagar.

Because the light and stained garments grasp loosely on her skinny body, and with down-cast eyes, she says: “I used to dream of flying excessive above the mountains, touching the blue sky as a flight attendant. Now, I’m caught in a nightmare, excessive on medicine, preventing for my life.”

Afiya, 24, is just one amongst 1000’s of individuals hooked on heroin within the disputed area the place a rising epidemic of drug habit is consuming younger lives.

A 2022 research by the psychiatry division of the Authorities Medical School in Srinagar discovered that Kashmir had overtaken Punjab, the northwestern Indian state battling a drug disaster for many years, within the variety of circumstances of narcotics use per capita.

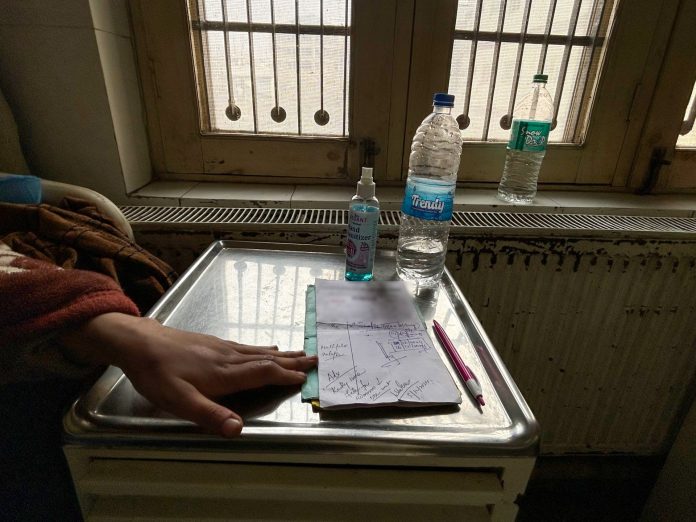

![The female addiction treatment ward at SMHS, Srinagar [Muslim Rashid/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IMG_1510-copy-1740483637.jpg?resize=770%2C513)

In August 2023, an Indian Parliament report estimated that just about 1.35 million of Kashmir’s 12 million folks have been drug customers, suggesting a pointy rise from the almost 350,000 such customers within the earlier yr as estimated in a survey by the Institute of Psychological Well being and Neurosciences (IMHANS) on the Authorities Medical School, Srinagar.

The IMHANS survey additionally discovered that 90 p.c of drug customers in Kashmir have been aged between 17 and 33.

SMHS, the hospital Afiya is in, attended to greater than 41,000 drug-related sufferers in 2023 – a mean of 1 particular person introduced in each 12 minutes, a 75 p.c enhance from the determine in 2021.

The surge in Kashmir’s drug circumstances was primarily fuelled by its proximity to the so-called “Golden Crescent”, a area overlaying elements of neighbouring Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, the place opium is grown on a big scale. Consultants additionally say power unemployment – triggered by the area dropping its partial autonomy in 2019, shortly adopted by the COVID-19 pandemic – fuelled stress and despair, driving Kashmiri youth in direction of substance abuse.

In consequence, says Dr Yasir Somewhat, a professor in command of psychiatry at IMHANS, hospitals and therapy centres within the area are stretched. He mentioned whereas habit therapy services have been established throughout Kashmir since 2021, solely a handful of hospitals have inpatient services for extreme habit sufferers like Afiya, who typically require hospitalisation.

‘It appeared innocent’

“You’re going to get by means of this,” Afiya’s mom, Rabiya*, whispers to her daughter, brushing apart the damp hair from Aafiya’s face. She has simply had a shower. Afiya’s father, Tabish*, sits on a chair in a nook, silently watching them.

Afiya barely listens to her mom’s reassuring phrases and appears extra targeted on repeatedly eradicating the blue blanket supplied by the hospital to let some contemporary air caress the deep, black wounds on her arms, legs and abdomen, brought on by the needle pricks in her veins from injecting heroin. The gaping wounds now ooze blood and a thick, yellow pus, as medical doctors warn she might infect her dad and mom and attendants.

Greater than six years in the past, Afiya was a brilliant high-school scholar dreaming of changing into a flight attendant. After passing her twelfth grade with spectacular 85 p.c marks, she responded to a job commercial posted by a number one non-public Indian airline.

“This isn’t the true me mendacity on this mattress,” Afiya tells Al Jazeera. “I used to drive my automotive. I used to be a trendy girl identified for my lovely handwriting, mind and robust communication abilities. My fast reminiscence made me stand out. I might recall particulars effortlessly, by no means lacking a factor. I used to be impartial and assured.

“However now, I lie right here immobile, like a lifeless fish, as my siblings put it. Even they’ll’t ignore the scent that lingers round me.”

She says she was chosen for the airline job and despatched to New Delhi for coaching. “I stayed there for 2 months. It felt like a brand new starting, an opportunity to fly, to flee.”

However her hovering goals have been dashed to the bottom in August 2019 when the Indian authorities scrapped the particular standing of Kashmir and imposed a months-long safety lockdown to discourage road protests towards the shock transfer.

Hundreds of individuals, together with prime politicians, have been arrested and thrown in jail. Web and different fundamental rights have been additionally suspended, as New Delhi introduced the area beneath its direct management for the primary time in many years.

“The state of affairs again house was grim. There was no communication with my household, no telephones, no strategy to know in the event that they have been protected. I couldn’t keep in New Delhi any extra, disconnected like that. I took every week’s go away and went house,” Afiya mentioned.

As she left the capital with assist from different Kashmiris, little did she know her journey as a flight attendant had ended even earlier than it started.

“By the point the state of affairs [in Kashmir] improved, roads opened up, and I might consider going again to New Delhi, 5 months had handed. In that interval, I misplaced my dream job, and with it, I misplaced myself,” she says as her eyes nicely up.

“I utilized for jobs in different airways however nothing labored out. With each rejection, I began dropping hope. Then COVID hit and jobs turned even scarcer. Over time, I misplaced curiosity in working altogether – my thoughts simply wasn’t in it any extra. I didn’t really feel like doing something.”

Afiya says that with every passing month, her frustration was despair. She started to spend extra time along with her associates, searching for solace of their firm.

“At first, we simply talked about our struggles,” she says. “Then it began with small temptations, with little puffs of hashish to cope with the strain. It appeared innocent. Then somebody provided me a foil [of heroin]. I didn’t assume twice. It felt euphoric.”

“The one factor that gave me peace was medicine – all the things else felt prefer it was burning me from inside.”

‘Ruthless starvation’

However the escape was short-lived, she says, and the cycle of dependence took over.

“The dream shortly was a nightmare. The euphoria light and was changed by a ruthless starvation,” she says as she describes the determined measures and dangers she started to take to search out medicine.

“As soon as, I travelled 40km (25 miles) from Srinagar to south Kashmir’s Shopian district to satisfy a drug seller. My associates have been operating out of inventory and somebody gave me his quantity. I referred to as him instantly to rearrange the availability. He was an enormous seller, and at the moment, the one strategy to get what we wanted.

“After I reached there, he launched me to one thing referred to as ‘tichu’ [local slang for injection]. He was the primary particular person to introduce me to injecting medicine. He injected it into my stomach proper there within the automotive,” she says. “The frenzy was intense – it felt like heaven, however just for a second.”

That second of euphoria marked the start of her fast descent into deeper habit.

“Heroin’s grip is cruel. It’s not only a drug, it turns into your life,” says Afiya. “I’d keep up all evening, coordinating with associates to verify we had sufficient for the subsequent day. It was exhausting, however the craving was stronger than all other forms of ache.”

Heroin is the area’s mostly used drug, with addicts spending 1000’s of rupees each month to purchase it.

“Heroin has unfold far and broad, and we’re seeing a disturbingly excessive variety of sufferers affected by it,” says IMHANS’s Somewhat.

The professor says he has famous an increase in substance abuse amongst girls, attributing it to psychological well being struggles and unemployment.

“Earlier than 2016, we not often noticed circumstances involving heroin. Most individuals used hashish or different delicate medicine. However heroin spreads like a virus, reaching everybody – males, girls, even pregnant girls,” he tells Al Jazeera. “Now, we see 300 to 400 sufferers every day, each new circumstances and follow-ups, and most contain heroin habit.”

However why heroin?

“Due to its speedy and intense euphoric results”, says Somewhat, “which many discovered extra quick and pleasurable in comparison with morphine”.

“It’s simple to make use of, has greater efficiency, and the misperception that it was safer or extra refined than different medicine solely added to its enchantment, regardless of its extremely addictive nature.”

‘Wired to hunt one final shot’

For addicts like Afiya, who has been admitted to rehab 5 occasions to this point, the combat towards heroin is a every day and uphill battle.

“Each time I go away the hospital, my physique pulls me again to the streets,” she says. “It’s like my mind is wired to hunt one final shot.”

Afiya’s intentions to get better stay unsure. She has steadily left the hospital throughout rehab to hunt heroin, or requested different sufferers for it throughout her every day stroll on the hospital.

“Drug addicts have a means of connecting with one another,” Rabiya, her mom, tells Al Jazeera. “I as soon as noticed her speaking to a male affected person in English and I realised she was asking him for medicine.”

Rabiya says she as soon as discovered medicine hidden behind the flush in a girls’s bathroom. “I discovered the stash and flushed it, however she [Afiya] nonetheless managed to get it [heroin] once more,” she says. “She is aware of tips on how to manipulate the system to get what she desires.”

A nurse on the SHMS rehab revealed how sufferers typically bribed the safety guards. “They offer them cash or give you excuses to depart, even whereas on treatment,” says the nurse, requesting anonymity as she will not be allowed to speak to the media. The feminine ward is close to the hospital’s entrance – that too makes it simpler for sufferers to slide out unnoticed, she says.

“It’s heartbreaking as a result of we attempt to assist, however some sufferers simply discover methods to depart.”

“She [Afiya] escaped one evening and got here again the subsequent day, having spent hours with male sufferers who helped her get heroin,” says a safety guard, who additionally didn’t want to disclose his id for worry of dropping his job.

However Afiya stays defiant. “These medicines don’t carry the peace I get from a single shot of heroin,” she tells Al Jazeera, her arms trembling and her nails digging into the hospital mattress.

The bodily toll on her physique because of habit has been extreme. Open wounds on her legs, arms and stomach ooze blood. When Dr Mukhtar A Thakur, a plastic surgeon at SMHS, first examined her, he says he was shocked.

“She was unable to stroll due to a deep wound on her non-public elements and a big scar on her thigh. She had critical well being issues, together with broken veins and contaminated wounds. Her liver, kidneys and coronary heart have been additionally affected. She struggled with reminiscence loss, anxiousness and painful withdrawal signs, leaving her in a vital situation,” he says.

Afiya’s dad and mom say bringing her to the rehab at SMHS was a determined transfer. “To guard her and the household’s repute, we instructed our kin she was being handled for abdomen points and scars from an accident,” says Rabiya.

“Nobody marries a drug addict right here,” she provides. “Our neighbours and kin have already got doubts. They discover her scars, her unstable look and the repeated hospital visits.”

Afiya’s father says he typically hides his face in public, “unable to bear the disgrace”.

Well being specialists say searching for therapy for drug habit stays a problem for Kashmiri girls as social stigma and cultural taboos preserve many ladies within the shadows.

“Rehabilitation for ladies is commonly carried out secretly as a result of households don’t need anybody to know, and in Kashmir, everyone is aware of everyone,” Dr Zoya Mir, a scientific psychologist who runs a clinic in Srinagar, tells Al Jazeera.

“Many rich households ship their daughters to different states for therapy, whereas others both endure in silence or delay therapy till it’s too late,” she says. “These girls want compassion, not judgement. Solely then can they start to heal.”

*Names have been modified to guard identities.